‘There’s a charm in the sound, which nobody shuns

Of smoking hot, piping hot, Chelsea Buns’

Eighteenth century song

Reading Elizabeth David’s English Bread and Yeast Cookery is like visiting the most eclectic bakery you can imagine and being given a taste of every development in British baking from the middle ages to the modern day. As she rolls out the history of every bun, cake and bread,she puts them in context, describing where they came from and how they were invented or discovered. The book I have was bought for me by my mum and for me, is the ultimate guide to bread and yeast cooking.

This book is amazing. Sometimes it takes a few goes to actually get a grip on a recipe and it always takes a couple of thorough readings, but because they are such a joy to read, this is no bad thing. That said, they are not always the easiest recipes to follow, for example the recipe for Chelsea Buns tells you to follow the method for Bath Buns on the previous page which is rather confusing when they contain different ingredients in different quantities! However, my first batch of Chelsea Buns turned out exactly as I remember them, therefore, exactly as they should be.

Before we begin, I’ll pay homage to the great Elizabeth David by filling you in on the history of the wonderful and decadent and apparently ‘friendly’ (according to my friend who assisted with the baking) Chelsea Bun, in her own words. Hopefully this excerpt will whet your appetite to go out and buy this lovely book and explore it for yourself. It certainly makes me want to open a cafe in the style of the wonderfully described Chelsea Bun House…

“The famous Bun House of Chelsea was probably build towards the end of the seventeenth century or in the early years of the eighteenth. It was a large establishment, situated near Sloane Square in what was then Jews Road, later the Pimlico Road, and within easy reach of the river. Evidently a bakery, pastry cooks’ and refreshment shop combined, the Bun House provided tables at which the customer could sit down and eat their cakes and buns fresh from the oven. In its early days the Bun House was renowned chiefly for its hot cross buns, sold in massive quantities on Good Fridays and during Easter celebrations, when great crowds flocked to Chelsea expressly to visit the Bun House. Caroline of Ansbach, Queen of George II, was a frequesnt visitor to Chelsea during the early years of the reign (he succeeded in 1727) going there by water – tradition has it that she, her family and the King himself visited the Bun House on many occasions. Possibly, then, the popularity of the Chelsea bun , as distinct from the older and more famous Good Friday buns, dates from the days of Hanoverian royal patronage, although already in the days of Queen Anne, Swift, staying at Chelsea for a change of air, reported to Stella how ‘Rrrrrrrare Chelsea buns’ were cried in the streets, and how the one he bought for a penny was stale adding, not surprisingly, ‘I did not like it’ (1) [This exchange refers to Jonathan Swift, author of Gulliver’s Travels among many many other things, and ‘Stella’, real name Esther Johnson, who was his student, the daughter of a servant of a friend of Swift’s and they remained in rather ambiguous contact for the rest of Stella’s life.]

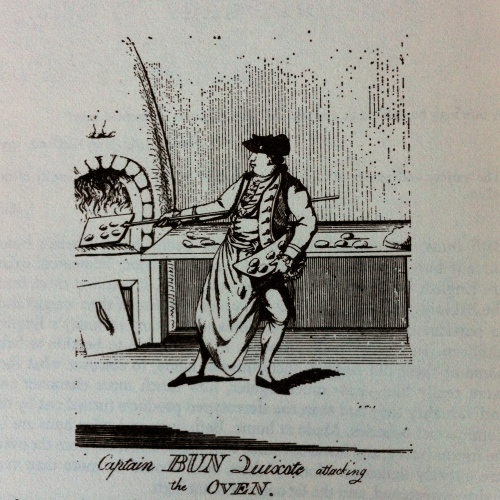

A century after Swift’s brief stay in Chelsea, the Bun House was still flourishing. For four generations it was in the ownershp of a family called Hand [see illustration below] and according to Chamber’s Book of Days ‘families of the middle classes’ would sill walk a considerable way to taste the delicacies of the Chelsea Bun House (2). Demolished in 1839, the original Pimlico Road Bun House was re-created in Sloane Square for a brief period in 1951 as part of the Festival of Britain celebrations.

For four generations the Chelsea Bun House belonged to a family called Hand. One of them became an officer in the Staffordshire militia. Inevitably he was nicknamed Captain Bun. From a print dated 4 January 1773; Chelsea Public Library

‘It is singular’ wrote Sir Richard Phillips (1), an addict of the original Chelsea buns, ‘that their delicate flavour, lightnedd and richness, have never been successfully imitated… for above thirty years I have never passed the Bun House without filling my pockets’

Sugary, spicy, sticky, square and coiled like a Swiss roll, the Chelsea bun as we now know is a pretty hefty proposition. That it can be very usefully adapted to smaller scale needs was demonstrated to me in the letter quoted further on. So it worth knoing the principle on which Chelsea buns are made. Recipes vary considerably in details, the but the basic bun dough is fairly constant…”

1. Journal to Stella, 2 May 1711

2. Chamber’s Book of Days, Volume 1, 1869 *

So now we can proceed with the recipe, but in my own words…

Chelsea Buns

Dough

550g flour

2 eggs

225g butter, softened

150g milk

15g yeast (or 1 sachet of dried yeast)

Grated peel from 1 lemon

1tsp cinnamon

1tsp salt

2tbs sugar

Filling

85g currants

85g butter

85g soft brown sugar

85g castor sugar

1tsp cinnamon

Glaze

1tbs milk

2tbs castor sugar

First make the dough:

Warm the milk very slightly in a pan and then pour a little over your yeast in a bowl. This activates the yeast and should make it bubble a little and become smooth. If you are using dried yeast, it will dissolve and become silky.

Mix the salt and sugar into the flour then rub the softened butter into this mix until it resembles breadcrumbs (rather like when you make a crumble)

Add the creamed yeast, eggs, milk, cinnamon and lemon peel and mix to a light dough. I would add the milk in increments until you have a stiff-ish dough that isn’t sticky. (If you are going by my mum’s description, it needs to look like a baby’s head! We always affectionately pat the ‘baby’ when it is ready…It makes a fat little sound: ‘plap plap’)

Now cover the bowl with cling film and leave it in a warm place for about 1 1/2 hours until it has roughly doubled in size. It’s quite a slow process with this dough, especially if you’re making it in winter so don’t be afraid to leave it a little longer.

While it is rising mix together the currants, sugars, and butter (cut into little pieces) to make the filling you do not want to combine the sugar and butter, but have each thing separate (see picture below)

When the dough is risen well, punch the dough down and then knead it well for about 5 minutes. I do this in the bowl but you can do it on a surface, just try not to add any extra flour as this will stiffen the dough.

Now divide the dough into 2 equal portions and roll each into a rectangle about 20cm x 30cm (it is important to try and keep them fairly square, I had trouble doing this but have a bash.

Sprinkle the filling over the rectangles, spreading it as close to the sides as you can

Now, fold the filled dough rectangles into 3 (as your would for puff pastry if you have ever made that) up from the bottom along the longest side so you have 2 short sausages. Seal the edge with a bit of milk or water and press together. Then give it one turn and roll the dough out again to roughly it’s original rectangle size

(can you see the smear of butter on my camera lens in these pics?!)

Now you make the final roll. Roll the dough up firmly along the shortest side (as you would a Swiss roll if you have ever made that) so you have 2 long sausages, seal the edge again and turn it over so the seal is on the bottom. (I forgot to seal mine so the square shape was a bit undone once they were baked, never mind, see pics below)

Now cut the sausages into your buns around 4cm thick (you can actually make them as small or big as you like but remember once they have proved and cooked they will be approximately double in size)

Arrange your buns in a greased dish or 2 (seven to a row used to be the rule of professional bakers) with about 4 cm between each bun. The spacing is important, for during the proving period the buns grow in size and move together assuming their characteristically square shape.. I didn’t leave quite enough space as I had so many (about 26 I think) and not enough tins! It didn’t seem to hinder them too much…

Now leave them to prove with cling film over the top in a warm place, until they are all but touching (probably around 45 mins but keep an eye on them)

Pre-heat the oven to 220 degrees or gas 7

When they have proven, sprinkle them with castor sugar and bake them for 15 minutes. during the baking, the merging process is completed. You want them to be golden brown and soft to the touch

Make the sugar and milk glaze by warming the milk and sugar in a pan until the sugar has dissolved

When they come out of the oven brush them with the glaze.

Leave them to cool for a couple of minutes then separate them with a knife and put on a wire rack. They are truly amazing eaten still warm, even hot. They are so soft, so sticky and fragrant you’ll probably eat them all in one sitting but make sure to invite some friends over and munch with a cup of tea while everyone goes silent. When there’s a warm Chelsea bun in the room, on your plate, in your mouth; nothing else matters.

They keep well in an air tight tin and can be quickly re-heated in a hot oven for a couple of minutes. They are perfect for breakfast.

The ‘letter’ Elizabeth David refers to in the excerpt above is a lovely thing, taken from correspondence she had with her lifelong friend, the painter Arthur Lett Haines with some incredible sounded alterations to the Chelsea bun which I really want to try:

” [He] always had interesting and beautifully imaginative ideas about food. He writes “I like Chelsea buns. But find them rather large and bucolic [Surely not?!]. So make them very small, exaggerate the quantitiy of fruit, chopped small, and serve them no larger than big petit fours, coated with Royal icing.

1. lemon-flavoured and peppered with a crushed pistachio

2. Royal icing flavoured with angostura and sprinkled with poppy seeds’

Now that seems to me a most admirable approach to the problem of re-creating a speciality which would otherwise have little place in our lives today” *

Now Elizabeth David, that is one thing we disagree on, I cannot imagine a world where the Chelsea bun would take a little place in my life today and I encourage everyone to disprove her theory.

*Excerpts from Elizabeth David’s English Bread and Yeast Cookery, Penguin Books, 1977, pg474-484

I ♥ Captain Bun! Look at his nonchalant stance as he slides those buns into the oven!

Although I doubt they could live up to Mum’s (and your) buns, I really want to visit this Church of the Chelsea Bun in Cambridge:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/lifeandstyle/2011/nov/11/fitzbillies-tim-hayward-cambridge

YES! I saw this too… Day trip??

And yes, isn’t Captain Bun the BEST! “Right you ‘orrible little buns, get ye in the oven and make it quick!”

Love chelsea buns, the Fourstation in London do great ones too!

*want that book*

Certainly going to try the Fourstation. Thanks for the tip! You really should get this book, massive recommendations from here

A couple of tips –

Never be tempted to overdo the quantity of yeast-I never use dried yeast either. If you ask nicely in a good baker’s shop they will sell you a piece of fresh yeast which should be a pale creamy brown colour. Divided up it freezes well and I used to freeze quarter ounce bits back in the imperial measures days when I baked all my own bread!

Too much yeast gives you dry bread.

Also you can overheat the dough during the proving stage and it will not rise, if by ‘a warm place’ you choose a hot one by mistake. The airing cupboard is good in the winter or near a radiator.A sunny spot in summer. Cover it like a baby and wait for it to grow!

I am now wondering about using the top of a woodburning stove to cook flat breads and griddle cakes etc-anyone tried this?

xx

Wise words from the master baker. My mum!

re: flat breads.. I think it will certainly work and be loads of fun… It’s worth a try. Just don’t get flour on that rug!

Pingback: Hot Not Cross Buns | annascafe